The Arnolfini Portrait

Jan van Eyck

1434, 82 cm × 60 cm (32.4 in × 23.6 in)

Oil on oak panel of 3 vertical boards

The National Gallery, London

Rich with detail, the Arnolfini Portrait painted by Jan van Eyck is a wonderful early example of the Northern Renaissance artists’ mastery of oil painting and their obsession with the behaviour of domesticated fabric. But while it may look like a straightforward double portrait, the Arnolfini is one of western art history’s greatest riddles.

Van Eyck’s The Arnolfini Portrait (also know as The Arnolfini Wedding, The Arnolfini Marriage, the Portrait of Giovanni Arnolfini and his Wife) is, quite literally, one of the single most famous paintings in the history of European art.

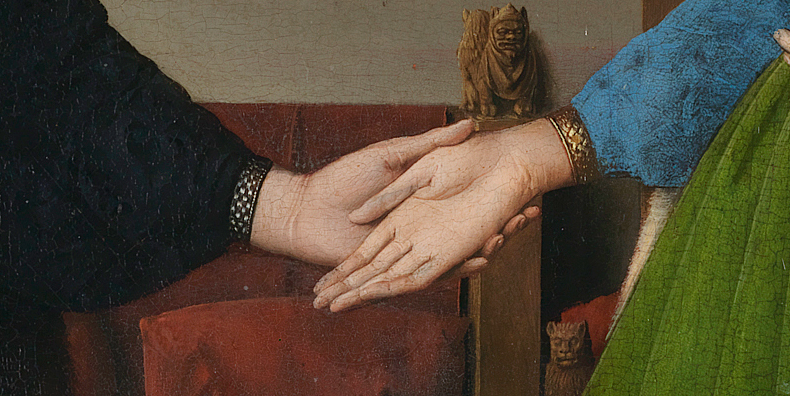

The full-length double portrait depicts a wealthy man and young woman in a darkened interior holding hands. The man’s right hand is raised up, as if in greeting or taking an oath, as he looks slightly to his left. The woman, with her head slightly downcast, looks directly at him. The subtle interplay of light and shadow creates an atmosphere of serene intimacy.

The identification of the figures was made in an inventory of Margaret of Hungary’s collection in 1516, which noted: “A large picture which is called Hernoult le Fin [translating to “Arnolfini”] with his wife in a bedchamber done by Johannes the painter.”

However, which member of the Arnolfini family and the identity of the woman long remained a puzzle. Like the numerous bust portraits van Eyck painted, it serves to illustrate the growing wealth and autonomy of the middle class in Flemish society.

In 1934, art historian Erwin Panofsky proposed that the painting depicts the vows of a marriage ceremony between the wealthy Arnolfini and his young wife. According to Panofsky’s theory of “disguised symbolism” every object in the scene was laden with iconographic significance. The small dog, for example, was not a beloved pet but a symbol of fidelity, and quite fitting for what the historian believed was a marriage scene. Additional images to support the notion of a marriage include the single burning candle in the hanging candelabra symbolizing the presence of God at this sacred event, the man’s cast aside clogs indicate that this event is taking place on holy ground, while the oranges on the chest under the window may refer to fertility.

Against the back wall of the room, there is a small convex mirror reflecting the back of the couple and two individuals who appear to watch the ceremony, one who appears to wear an elaborate red turban, or chaperon.

On the wall above the mirror the artist has written an inscription in elaborate script that says “Johannes de Eyck fuit hic 1434” (Jan van Eyck was here in 1434). This marks the only known example where the artist’s signature was on the actual painting rather than the picture frame. The red turban in the reflection, along with the distinctive signature, leads many to believe it is van Eyck in the mirror.

Panofsky did a good job proposing his theory. But here’s the snag: in 1990 a document came to light that certified the wedding of Giovanni di Nicolao Arnolfini occurred in 1447, 13 years after the portrait was painted and six years after the artist had died. As stated above, the artist has clearly written the date 1434 on the painting, in ornate Latin. As Giovanni’s wife died in 1433, this presents a possible hypothesis that van Eyck began the work in 1433 while his patron’s wife was alive but she had died by the time he finished it, or it was simply a posthumous portrait. This theory is supported by much of the content of the scene: the male figure’s loose grasp on the woman’s slipping hand, and the odd candles in the ornate chandelier – that on the man’s side is still whole and lit, while the opposite candle holder is empty aside from a few drips of wax, signifying that the man’s life light is still burning while hers has burnt out.

Another theory proposes that this is a depiction of a second marriage, for which the records have been lost. The woman’s face appears particularly young – although this youth is no indication that she was a second wife, as ladies could be married before they were even teenagers at this time. Her appearance is very fashionable, with a high, plucked brow and specifically styled hair.

Today it is widely agreed that the painting commemorates the young wife of Giovanni di Nicolao, Costanza Trenta, who died (possibly during childbirth) one year before the painting was complete. Her covered head expresses that she is a married woman – only the young, the royal, or the immoral would wear their hair loose and uncovered. Her downwards gaze also shows her submission and meek obedience to the man holding her hand.

All the ambiguity rather adds to the charm of the painting and demands that viewers look more closely at the beautiful, detailed workmanship in order to dig out their own ideas and theories about the work from independent visual analysis. Even if nothing but an appreciation of Jan van Eyck’s supreme talent can be concluded from this work, that is surely a satisfactory conclusion to take away from the mysterious Arnolfini Portrait. Perhaps, if its subject was known, with all of its details and intricacies, then the work wouldn’t be half as appreciated or investigated. Its charm lies in the stories and ideas which it inspires in the minds of those who look at it, into it, and dig beneath its surface; an absence of knowledge only adds to its beauty.

there is a detailed description of the symbolism on the artmejo website.

credits:

theartstory.org/artist/van-eyck-jan/artworks/

wikipedia.org/wiki/Arnolfini_Portrait